- BY ISSIMO

- October 27, 2023

Plenty of great Italian women have left an indelible mark on modern culture. Monica Vitti. Margherita Hack. Rita Levi-Montalcini.

A lesser-known figure – unless of course you work in design and architecture – that’s had an equally pivotal impact? Gae (Gaetana) Aulenti.

Often described as “l’architetto geniale” – the “genius architect” – the creative was, for much of her career, the most influential woman in Italy in a very male-dominated industry, as well as a pioneer in industrial, interior and exhibition design.

Her life, style, and achievements made her a trailblazer in her field, which is why we thought we’d put the spotlight on her this week. And if you feel inspired by what you read, you can always channel a little Gae creativity with our ISSIMO x L.G.R sunglasses – our own homage to the amazing architect and her signature round glasses.

The bright start of Italian architecture

Born in 1927 in Palazzolo dello Stella, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Gae Aulenti’s journey to architectural stardom was marked by determination and her wish to rebel against her parents’ desires for her to become “a nice society girl”.

She pursued her studies at the Milan Polytechnic, where she became one of the few women in her generation to graduate with a degree in architecture (she was one of only two female students in a class of 20). Her motive for enrolling was that she considered “architecture a useful profession,” especially in post-war Italy. She was right: her work would go on to bolster a renovated architecture for the country, and Europe at large.

On graduating in 1954, Aulenti joined Casabella magazine and quickly became part of the “Neo Liberty” movement that pushed for a revival of local building traditions and individual expression – something that she strove for in all aspects of her life, from her career to her personal closet. As she once told Women’s Wear Daily: “The moment it’s loudly announced that red is in fashion, I want to dress in green.”

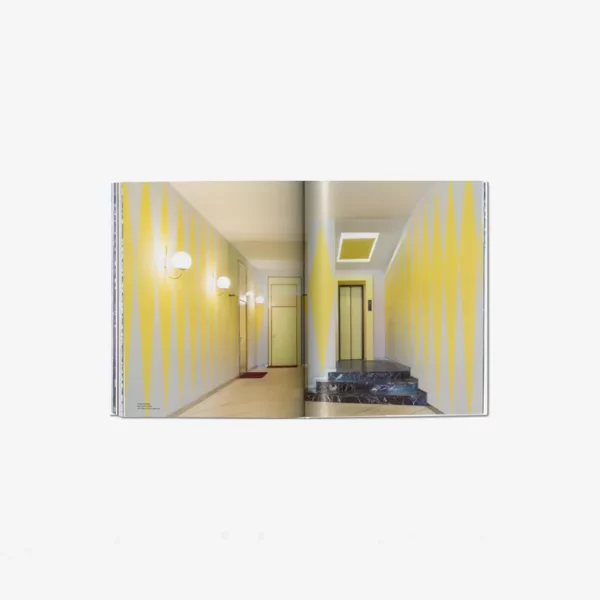

Olivetti’s Showroom. Paris, 1967. Credit to M. Rolly

Her skills and visions soon caught the attention of some of Italy’s biggest institutions and companies at the time. Fiat and Olivetti commissioned her showrooms both in Italy and abroad, La Scala in Milan asked her to design sets, and well-heeled Italians hired her to work on their private villas.

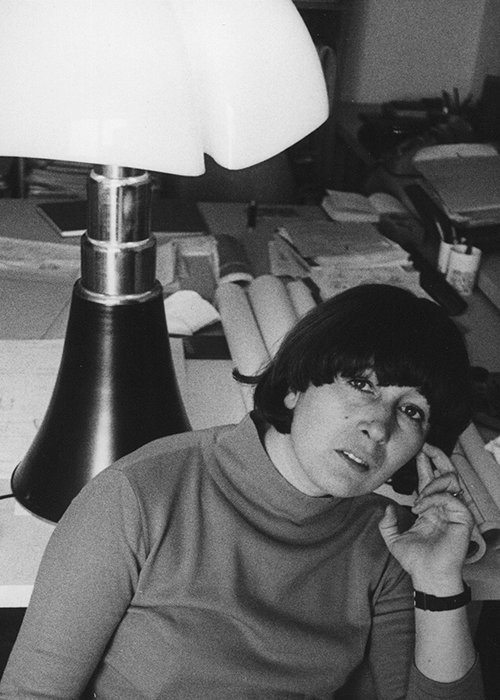

All the while, Aulenti developed a penchant for designing objects, too, many of which would end up becoming status symbols, despite the fact the architect wasn’t at all interested in trends and fame. She was the mastermind behind the Tavolo con ruote (Table with Wheels) and the Pipistrello (Bat) lamp – design icons that are still coveted today and considered classics of 20th century furniture.

Gae Aulenti with her creation: The Bat Lamp

Throughout the 60s and 70s, she also produced evergreen pieces for Milan’s major design houses, from Knoll and Kartell, to Zanotta, as well as lighting for Artemide, Stilnovo and Martinelli Luce.

But what Aulent is perhaps most known for is her spectacular transformation, starting in 1981, of the Gare d’Orsay train station in Paris into the Musée d’Orsay, which opened in Paris in 1986. The project was her largest and most divisive, turning the central hall, a grand barrel-vaulted train shed lit by arching rooflights, into an open exhibition space featuring modern industrial materials, from wire mesh partitions to new rough stone walls.

Not everyone loved the contrast between the old and new, but Aulenti, in her typical style, didn’t seem to care. “The press was very rude,” she said in an interview a few years after the opening. “But 20,000 people a day stand in line waiting to get in.”

Palazzo Grassi, Venice.

That contrasting approach between tradition and modernity – what she called “double ambiguity” – defined much of her portfolio, which besides the Musée d’Orsay, also included renovating Palazzo Grassi in Venice, designing the permanent collection galleries of the Pompidou Centre in Paris, the Palacio Nacional in Barcelona and, in the last years of her career, conceiving the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.

Throughout it all, she kept a fierce, independent stance on her design. “If everyone likes you, it means there is something wrong,” she used to tell herself.

Yet, 11 years since her passing in 2012, there seems to be unanimity in the architecture world as to just how important Aulenti has been for the sector.

It’s possible Aulenti would have known that would happen.“When you’re criticised for something, it’s best to wait two or three years and see,” she once said. Again, she couldn’t have been more right.